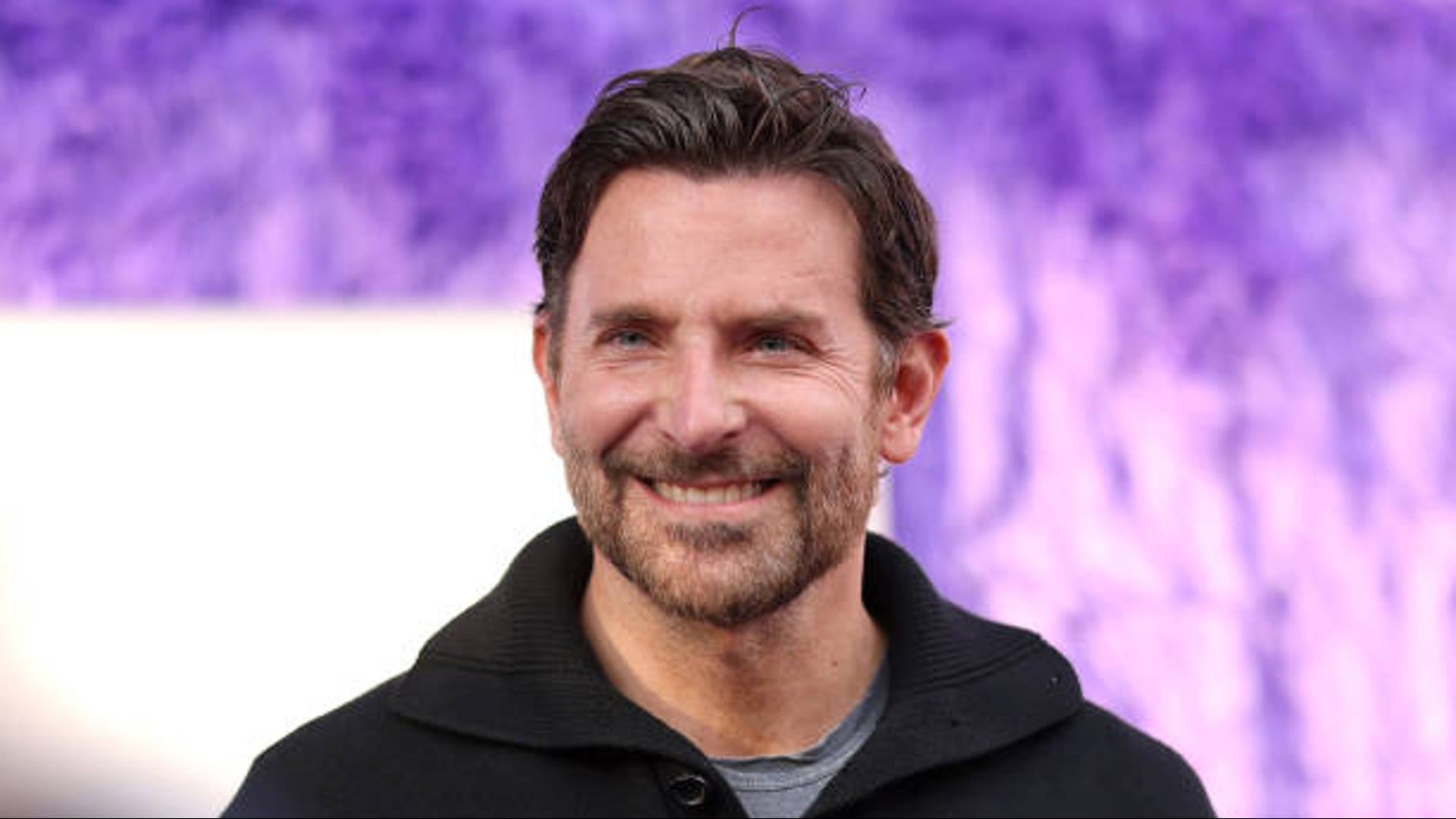

Bradley Cooper new documentary sheds light on caregiving crisis

A new documentary, “Caregiving,” executive produced by Oscar-nominated actor Bradley Cooper, will explore the hidden struggles of caregivers.

unbranded – Entertainment

Jami Chapple feels stuck.

At 54, the single mother has no income and is two months behind on rent. She’s behind on her utility bills, too, and can’t find work because she’s busy caring for and homeschooling her 12-year-old son who is autistic and has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

“It’s so draining that there’s no way to financially produce,” Chapple, who lives in Wyoming, said. “Even if you want to.”

The last time Chapple felt this stuck was around 2005. She was raising four children then and needed help finding food and clothes for her family, so she dialed the 211 helpline, a national program supported by United Way Worldwide that connects callers to local experts who can refer them to health and social service organizations in their community.

“That lady took so much time, with such patience,” Chapple said of the 211 call taker. “She gave me dozens and dozens of resources.”

Chapple called 211 this time, too. But she said she wasn’t eligible for the services the helpline referred her to, and the caregiver support group they connected her with is too far from her home.

The 211 helpline is expanding services for caregivers like Chapple. But with 53 million caregivers in the U.S., according to a 2020 report by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving, it’s not nearly enough − especially if the services 211 refers callers to start to dwindle, said Bob Stephen, vice president of health security programming at AARP.

Life for caregivers might get even harder if the Senate passes President Donald Trump’s so-called “big beautiful bill” which includes massive cuts to Medicaid. The proposal includes work requirements for people under 65 to access Medicaid, “many of whom would be family caregivers,” said Nancy LeaMond, AARP’s executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer.

In 2021, in partnership with AARP, 211 met the caregiving crisis by adding a Caregiver Support Program in a handful of states including Florida, Texas, Michigan, Pennsylvania, South Dakota and Wisconsin. The program grew in the years that followed, and now millions more caregivers will have access to caregiver-specific support assistance as the program is being expanded to 10 more states: Alabama, Iowa, Kansas, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Missouri and Illinois, plus Puerto Rico. The full list of participating states and regions can be found here.

Specialists help with callers’ most immediate needs like food and shelter, and then get them connected to other programs that specialize in long-term support. There are about 5,000 211 phone workers nationwide, said Heather Black, vice president of 211 System Strategy at United Way Worldwide.

“We’re the triage,” Black said. But what happens when the triage isn’t enough?

211 helps caregivers who don’t know they are caregivers

Since 2021, the 211 Caregiver Support Program has helped more than 1 million caregivers through a combination of direct support, local community engagement and website visits, according to United Way Worldwide.

Caregivers often say they didn’t know they were a caregiver at the time, including celebrity caregivers like Bradley Cooper and Uzo Aduba. So when 211 specialists speak with people in need, Stephen said, they don’t ask the obvious question, “Are you a caregiver?”

Instead, call takers are trained to listen for cues that indicate the person is a caregiver.

“It’s amazing how much information people share as they tell you their story about their situation,” Black said.

“You don’t use the word caregiver until you’ve got them recognizing some of the tasks that they do,” Stephen said, like driving older parents to medical appointments.

Callers might ask about food, housing or utility assistance, which were the most common requests out of the nearly 17 million 211 helpline calls last year. If the caller indicates they may be a caregiver, then there are a slew of other resources 211 workers can direct them to, like transportation services, veterans’ benefits, respite care, meal delivery programs and caregiver support groups.

Evidently, though, some well-meaning attempts to connect people with programs are falling flat. And that may only get worse if funding cuts rattle the caregiving community’s resources.

More help is needed, caregivers and advocates say

The 211 helpline is designed to connect people to resources already in their community. But if the resources people need aren’t available in that region, there’s not much 211 can do, Stephen said.

Chapple said 211 was helpful when she was raising her four older children back in the early 2000s, when she lived in Texas. But now that she’s in Wyoming and raising a kid with a neurodevelopmental disorder, she’s hitting roadblocks. Some of the referrals she got recently through 211, Chapple said, she was not eligible for.

“There’s not a lot of resources for my situation,” Chapple said.

Chapple said she doesn’t have family support like other caregivers. And she’s had a hard time finding a job that offers the flexibility she needs to care for her son. Her biggest needs now, she said, are rent assistance and help finding work. But she said some programs require more time to apply than caregivers have.

“There is an immense amount of time wasted for caregivers on forms,” Chapple said. “Filling out forms, phone calls, research, paperwork, interviews with the health agencies and even just the emotional preparation to do those things is sometimes distressing.”

The 211 helpline doesn’t rely on federal funding, Stephen said, “although the federal budget does fund many of the things that 211 connects people to.” He’s worried federal cuts could further reduce the programs available for people in need, including caregivers.

“211 is going to be more critical,” Stephen said. “Because people aren’t going to really understand what is still there.”

Caregiving is a labor of love, Chapple said. But it’s difficult physically, mentally, financially and emotionally. She said she’s had to give up a lot of the simple pleasures she used to enjoy, like taking a relaxing bath or writing songs. Sometimes, she said, she sits in her car for just 10 minutes to listen to music. That brings her some peace.

“There’s no time for us,” Chapple said. “There’s no time for self-care. I mean, I’m lucky if I get like a shower or two a week.”

Madeline Mitchell’s role covering women and the caregiving economy at USA TODAY is supported by a partnership with Pivotal Ventures and Journalism Funding Partners. Funders do not provide editorial input. Reach Madeline at memitchell@usatoday.com and @maddiemitch_ on X.