There was no closure. There were just questions I had no answers to and the ache of loss – sore and throbbing and made no less cruel by the passage of time.

The surprising origins of Father’s Day

The very first Father’s Day in America was celebrated on June 19, 1910, in the state of Washington.

unbranded – Lifestyle

I wasn’t sure I really wanted another box of my dad’s things.

That’s not true. I knew I didn’t want them. His friends and family, historically, tend to give me what once belonged to him. His memories. His jokes. His artwork. They think I want these because I’m his son.

I’ve always resented that.

I saw it differently – more of a one-way transaction of a burden. “Take these off my hands,” they seemed to say. “Let me let this go.”

Father’s Day intensifies my grief

These feelings swelled, like clockwork, the closer I got every year to Father’s Day.

We all have our dates, our burdens, that land less gently than the others. And Father’s Day always landed like a heavy yoke over my shoulders.

I carried the grief because I thought I had to. I was his son – so wasn’t it my responsibility? I took it on like a debt – though it was one I, myself, had never incurred. He left when I was 8 years old. My only sin was being his son. Somebody had to be there in a way he never had been, right?

I started running out of spaces to tuck the plastic containers and cardboard boxes where I couldn’t see them. I exhausted verbal sidesteps of comparisons between us. My resentment toward them – the old belongings, the people who gave them to me, my dear old dad – just grew.

Tucked into one of those boxes is his coroner’s report. It says what I already knew: chronic ethanolism.

My dad was an alcoholic. What had long been coming finally came, and suddenly everyone was released from their obligation to hold on to what had once been his.

So I waffled between acceptance and resentment. After he exited my life, he spent the better part of a decade homeless on the streets of Phoenix before my own sense of obligation brought me back to him. I should talk to him, I thought, just in case something changed.

It didn’t. Of course it didn’t.

Certainly not the stories, at least. When we talked on the phone, those fleeting few times between reconnecting and the death, I listened dutifully to the same repetitive narratives about concerts he’d worked security for. Songs I should check out. Movies I should watch. Things that slipped through the grasp of my memory – or concern – almost the moment he uttered them.

Those stories – they were exhausting to listen to, but I entertained them. Perhaps out of the same sense of obligation of everyone else. Or maybe they genuinely cared. The myopia of my resentment precluded me from knowing one way or the other.

There is pain in caring for someone in the cycle of addiction

One of the greatest cruelties of caring for someone with addiction is the cycles of grief before they’re ever truly gone. I spent days, weeks, months, stuck in the spiral of bargaining. What if I could think of the perfect thing to say to him to pull him from his own pattern, addiction, and bring him back to reality? What if I could accomplish what all his other friends and family couldn’t achieve – what if I could be a hero in his story? Who was to blame? What could I do?

But those perfect answers, perfect lines of thought, perfect lines of action never came to me.

And then he died.

There was no closure. There were just questions I had no answers to and the ache of loss – sore and throbbing and made no less cruel by the passage of time.

I resigned myself to the unknowing until I got a Facebook message from the owner of the autobody shop my dad frequented. He was closing his shop. He had a box of Dad’s things. He wanted to send them to me. It wasn’t a question of if I wanted them. Like everything else, of course I’d take them. Maybe they would make sense to me, someday.

When the package arrived, I peeled back the packing tape. The note – scrawled all-caps in bold black marker on a manila file folder: “We all loved Doug – he was my best friend.”

Inside: Smeared, nasty pieces of paper stuck together in heaps. Composition notebooks with just the first two pages full. Notes from doctor appointments: no sardines, no bologna, salami or stews. Smoked baby clams and albacore tuna, though, are perfectly OK. Shopping lists, started over and over again like he kept misplacing what he wanted: honey mustard, Snyder’s BIG (underlined, three times) sourdough pretzels, and salt and vinegar chips.

And the art.

My father was an artist. These works painted a different picture.

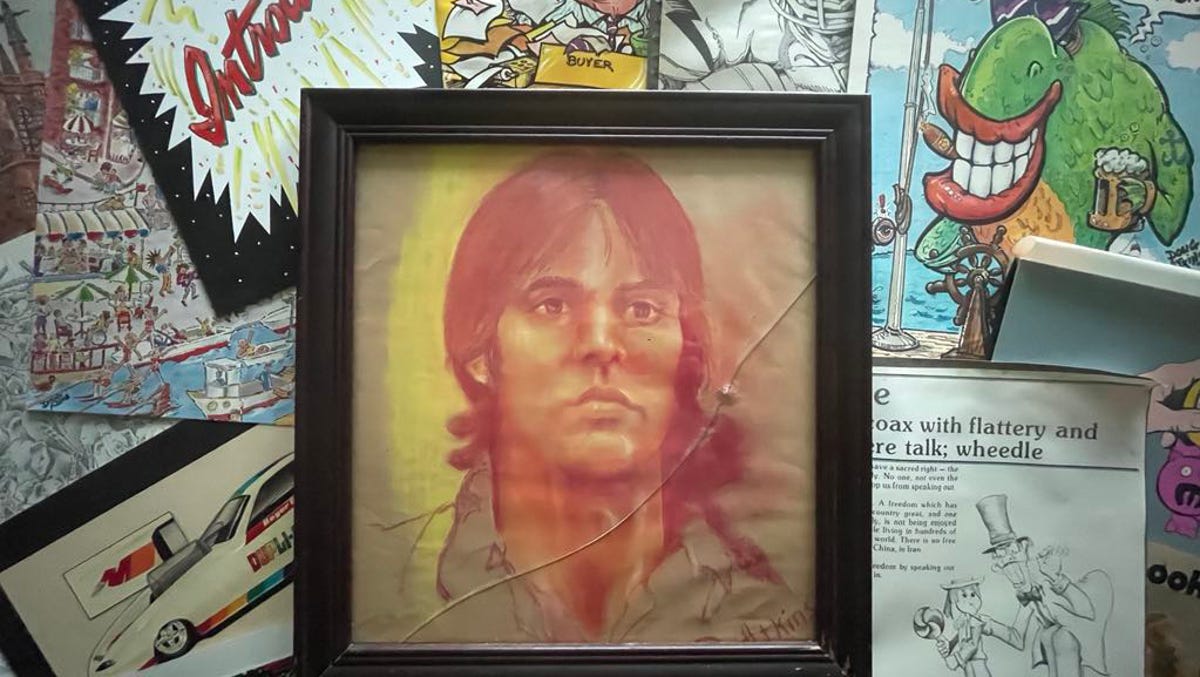

One thing about my father: He was an artist of undeniable talent. A nearly photorealistic chalk pastel portrait hangs in a cracked frame on my wall. On another, a pen-and-ink sketch of a skier, crouched low and skis together as if in mid-flight. And even as his disease ate away at his brain, his artistic talents persisted. Colored pencil-clowns, bold marker caricatures of Rambo and mockups of greeting cards he thought he could sell to some of the big-name companies filled this box, so overflowing from their own file folders that fitting them back in proved impossible.

And lists.

“For the record: Places I’ve been to,” one reads. Chicago, Tucson, Pittsburgh, Las Vegas.

“War favs,” reads another: A Bridge Too Far. Apocolypse Now (sic). The Wind Talkers (sic, again). “In Your Ear DJ Service,” one piece of dirty notebook paper reads. “Doug’s Pix ‒ Dance.”

I queued up Frankie Valli and The Clash and Iggy Pop while I sorted through the detritus of a life in decline.

I found my dad in what he left behind

His drawings, his sketches, his notes and jokes scrawled in his spaced-out, all-caps scribble vary from nonsensical to outright crude. But buried in the piles of dirty, disintegrating papers were the lists of those concerts he worked security for. Songs I should check out. Movies I should watch. I could imagine him writing those out, holding on to those scraps of himself, running his finger down the list and telling his son. I had back what I thought I’d long lost. It is the closest I can ever get to him again.

“Hey buddy,” he used to say. “Have you ever heard of …”

It took the least polished assembly of his work to finally get the full picture of his portfolio. I could understand much better now what everybody else had tried to get me to see with all of his belongings. The full weight of his illness finally sunk in. Here was a person who was trying, in his own, broken way, to make things right – like he used to promise me in the letters he sent when he moved, before they eventually stopped. I had always just been grieving what I had already lost.

These people weren’t trying to pass on their obligations. They just wanted me to see him with the kindness they did. And really, I couldn’t. Not fully. Not until now.

Drew Atkins is an opinion digital producer for USA TODAY and the USA TODAY Network. Reach him at aatkins@gannett.com.