Anker portable chargers are on sale for up to 50 percent off

There’s a big Anker sale on Amazon that covers several well-regarded power banks and charging…

There’s a big Anker sale on Amazon that covers several well-regarded power banks and charging accessories. This includes the 737 portable laptop charger, which is just $88. That’s the best deal of the bunch, as the price represents a 41 percent discount. The 737 is a 24,000mAh charger that can juice up a laptop, but…

How to save time while grocery shopping Cut grocery shopping time in half with these tips. ProblemSolved, USA TODAY Retail egg prices have fallen, following declining wholesale prices after record highs earlier this year. The average retail egg price dropped to $5.12 a dozen, down more than a dollar from its March peak of $6.23,…

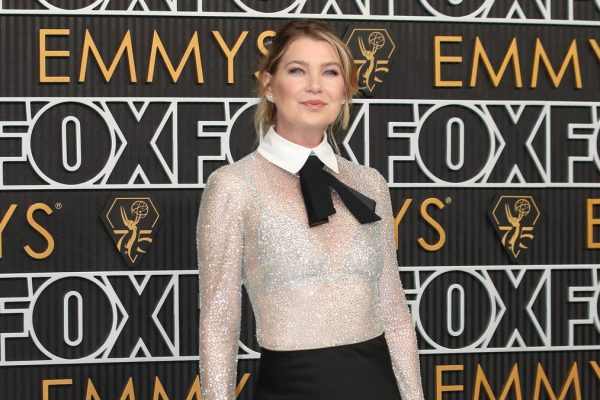

What you need to know about airport security rules and checkpoints Here are TSA rules that you need to know and what to expect at each airport checkpoint. Ellen Pompeo was detained by TSA for an hour due to organic sunflower seeds in her carry-on bag. TSA suspected a chemical on the packaging of the…

Tom Thibodeau did a fantastic job in New York, altering the way the Knicks are viewed as a team and franchise. He helped change the culture. But it wasn’t enough. New York Knicks move on from Tom Thibodeau and here’s why USA TODAY Sports’ Lorenzo Reyes explains why the Knicks chose to move on from…

West Hollywood Pride parade kicks off in colorful fashion West Hollywood held its annual pride parade in vibrant fashion. Matt Tolbert and his husband Joshua Gonzales knew they wanted kids for at least a decade. The New York thirtysomethings began their research into surrogacy and adoption and determined they’d need upwards of $100,000. “We didn’t…

NVIDIA releases a brand new video card and AMD follows up with a cheaper one. That’s basically been the cycle of the GPU industry for the last decade, with NVIDIA typically leading the pack and AMD rushing to keep up. But with the recent Radeon RX 9070 and 9070 XT, AMD finally found a winning…

Tour Disney’s private oasis at Castaway CayTravel

One of the most durable players in NFL history − though he was perhaps best known for an infamous blunder − has died. The Minnesota Vikings announced the passing of longtime defensive end Jim Marshall on Tuesday. A cause was not revealed, though the team said Marshall’s death came “following a lengthy hospitalization.” He was…

Matthew Cauli had no one to turn to when his wife, Kanlaya Cauli, had a stroke and was diagnosed with cancer during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. He left his graphic design career to care for her and their young son, Ty. Cauli said he quickly discovered there were few resources for caregivers. He…

Car recalls: Why they happen and what buyers should know Why do car recalls happen? Here’s what to know if your car has an open recall. Ford Motor Company recently issued multiple recalls, affecting over 42,000 vehicles, for issues that can potentially increase the risk of fires and crashes, according to the National Highway Traffic…