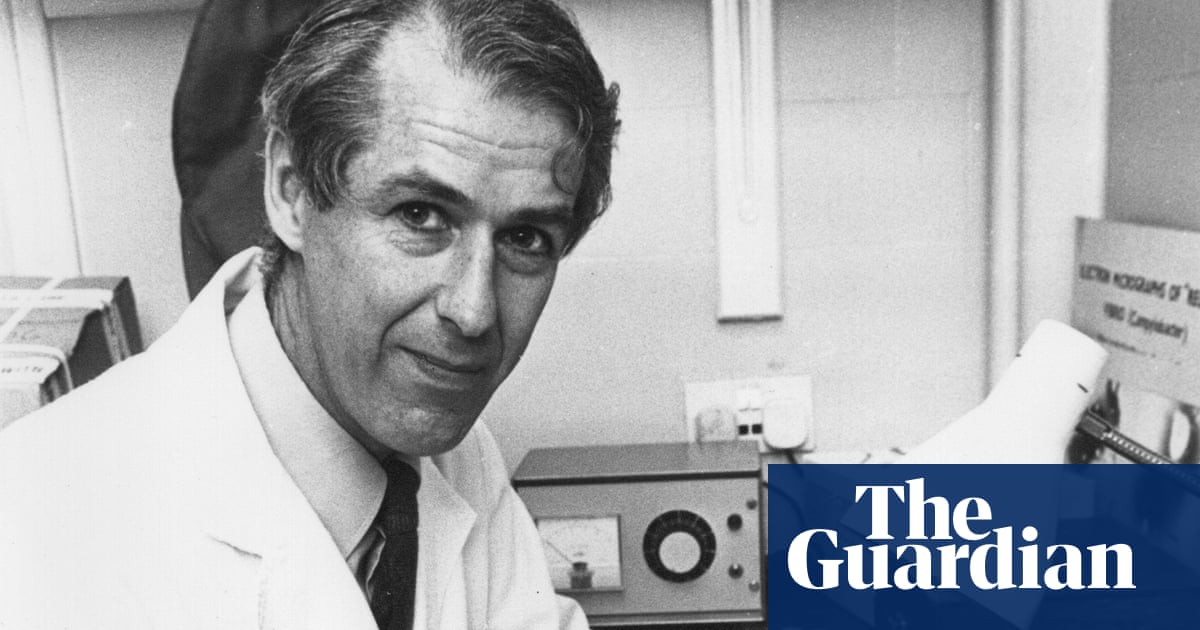

One Sunday morning in 1975, the clinical microbiologist Martin Skirrow, who has died aged 95, was checking a blood sample from a severely ill one-month-old baby in his laboratory at Worcester Royal Infirmary.

His microscope revealed “a melee of tiny darting rods” with a spiral shape enabling them to corkscrew their way into mucous membranes. What he saw were campylobacter bacteria, and he later wrote that “few are fortunate enough to stumble fortuitously on something that has such far-reaching consequences”.

At the time campylobacter was familiar to vets, as it often infects chickens, sheep and cows. But there was little mention of it in medical literature. After discovering the bacteria in the blood sample, Skirrow came across the work of the Belgian doctor Jean-Paul Butzler, who claimed to have isolated campylobacter in 5% of children with diarrhoea.

Infective organisms were believed to cause 10% of cases of diarrhoea, implying that campylobacter was therefore very significant, perhaps causing half of all infectious diarrhoea cases.

However, isolating and culturing campylobacter in the laboratory was tricky, and Butzler had only managed to do so by filtering infected faeces through extremely fine membranes, a difficult and time-consuming process.

Looking for a more user-friendly method, Skirrow created a “selective culture medium” of agar jelly that contained antibiotics to kill off competing organisms from any sample, as well as items to promote the growth of any campylobacter bacteria present.

In this way it became much easier to grow campylobacters. As a result, it soon became apparent how widespread campylobacter was as a cause of diarrhoea. Skirrow’s medium – known as Skirrow Campylobacter Selective Agar – is still widely used in laboratories.

In 1977 Skirrow published an article entitled Campylobacter Enteritis: A “New” Disease in the British Medical Journal, identifying campylobacter as a much more common cause of diarrhoea than previously thought, and showing that culturing of the bacteria and diagnosing infections should now be a much simpler matter thanks to the use of his selective medium.

The article became one of the 10 most frequently cited papers the BMJ has ever published and, from being little more than a footnote in medical textbooks, today campylobacters are studied as the most common cause of bacterial diarrhoea worldwide.

Skirrow was born in Naunton, Gloucestershire, the younger son of Marjorie (nee Vaughan) and Geoffrey Skirrow, who jointly ran the Granta hotel in Malvern, Worcestershire. From an early age he was captivated by nature and the intricate world of insects and plants that he could see through his microscope. He attended Oundle school in Northamptonshire, where he enjoyed biology and contributed an article about moths to the school magazine.

At Birmingham University, Skirrow studied medicine, qualifying in 1952. National service followed, and, having been a keen member of the university air squadron, he entered the RAF as a medical officer.

Posted to Iraq and Pakistan, he was inspired to specialise there in tropical medicine, and after he was demobbed he undertook a PhD in malaria at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Visiting his mother, who had been hospitalised by a bad accident, in Worcester Royal Infirmary, he met the ward sister Mary White. The pair married in 1957 and had two children, Helen and Andrew.

Skirrow’s work in tropical medicine took the young family to Ibadan in Nigeria, but when Mary became seriously ill 15 months later, they returned to the UK, where Skirrow decided to make his career instead. He became a junior doctor in haematology and bacteriology at Birmingham Children’s hospital, working with the microbiologist Keith Rogers, who had been trained by Alexander Fleming.

In Birmingham, Skirrow studied proteus bacteria and group B streptococci before being appointed to Worcester public health laboratory, which was attached to the Royal Worcester Infirmary, as a consultant microbiologist. He remained in charge of the laboratory until his retirement in 1989, running it single-handedly until 1983.

It was in 1983 that Skirrow first played a supportive role in research that eventually resulted in the Australian doctors Barry Marshall and Robin Warren being awarded the Nobel prize in physiology or medicine for their discovery of the role that bacteria plays in gastritis and stomach ulcers.

Back in the early 1980s gastroenterologists believed a surfeit of stomach acid was to blame for both, but Marshall and Warren suspected that a bacterial organism might be the cause.

It was a controversial standpoint, but Skirrow took their hypothesis seriously and, when the two were refused a request to address the Gastroenterological Society of Australia, he invited Marshall to address an international meeting he had set up: the European Campylobacter Symposium in Belgium.

While on his trip to deliver the speech, Marshall visited Worcester and, at an endoscopy session at Worcester Royal Infirmary, he and one of Skirrow’s assistants managed to isolate the offending bacteria, which they named Campylobacter pylori (later Helicobacter pylori).

The Lancet proved reluctant to publish Marshall and Warren’s research as it could find no doctors willing to peer review it. Once again Skirrow stepped in, contacting the journal to confirm the findings, and in June 1984 the pair’s paper was published, setting off a long journey that led to Helicobacter pylori being confirmed as a prime cause of gastritis and stomach ulcers, and Marshall and Warren winning the Nobel prize in 2005.

In retirement Skirrow continued to attend international campylobacter conferences and wrote or co-wrote numerous papers and book chapters on the subject.

His other passion was natural history and etymology. After his wife died in 2007, he lived with his daughter on her farm, a site of special scientific interest, where he enthusiastically made surveys of moths and insects for the Worcester Wildlife Recorders and discovered a new species of spider.

He also loved making model aeroplanes and was very musical, taking up the French horn and then the bassoon. He played all over the Midlands as a member of the Crooks Anonymous bassoon quartet.

He is survived by Helen and Andrew, and three grandsons, Oliver, Tom and Will.