Michael Sheen walks into a post office in Port Talbot and asks to withdraw £100,000. “That would be nice,” says the young woman behind the till. Then it dawns on her that he’s not joking. “Can I do £100,000?” she asks her colleague. She cannot.

“I loved that so much. She was really funny,” says Sheen. Filmed for a new Channel 4 documentary, Michael Sheen’s Secret Million Pound Giveaway, this was part of the actor’s two-year project to use £100,000 of his own money to buy £1m worth of debt, owed by about 900 people in south Wales – and immediately cancel it.

He doesn’t know who they are (data protection stopped that), but he hopes that the programme will alert those who hadn’t realised their debts had been cancelled (the people who might have been ignoring the scary letters that come through the door), as well as shine a light into the dark corners of high-cost credit, and what happens when debts are sold on to collectors.

It feels more timely than ever, in a cost of living crisis where 20 million people are financially vulnerable – but this is an area Sheen, 56, has been working on since 2018, when he set up the End High Cost Credit Alliance. He became interested when he was still living in Los Angeles in 2016, and watched John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight show spend about $60,000 to buy up $15m worth of medical debt and wipe it. Wondering if he could do something similar, he found it was harder in the UK, but by then he was hooked – appalled at the way the poorest people were forced to use high-interest credit that had become impossible to pay off. Or, worse, were turning to loan sharks.

It’s not the jazziest of causes, Sheen agrees. There’s a bit in the show where he gathers people in a Port Talbot cafe and reveals the “heist”, as he calls it, trying to inject a bit of drama into a speech that also contains the phrases “the consumer credit industry” and “the Fair Banking Act”. But the issue affected him. “I think it’s like everything that I respond to,” he says when we meet in a studio where he’s doing the final bits of filming. “It’s that there’s just a basic unfairness.”

In 2021, Sheen declared himself a not-for-profit actor – a bit of a throwaway line, but one based on his conviction that he had a responsibility to put as much of his earnings as he could towards causes and projects. Much of that centres around his local community: in Port Talbot, where the last of the steelworks’ blast furnaces recently shut, people are struggling, and in south Wales, 30% of children live in poverty.

Sheen traces his change in focus to a decade earlier, when he staged his version of The Passion, the three-day epic, in Port Talbot. Working with 1,000 local people brought him into contact with many community organisations. “I was learning about what was going on that I was totally unaware of, growing up,” he says. (He was born in Newport but moved to Port Talbot with his family when he was eight.) He realised that it was “partly because you sort of didn’t want to know”.

It was painful to learn, for instance, about the town’s young carers – children who were looking after ill or disabled parents – and to see that among the few bits of support available was a small organisation that took them bowling or to the cinema once a week. Another woman who had lost her son, a schoolfriend of Sheen’s, had set up a small grief counselling organisation to fill a gap. “And then, a couple of months later, I come back and the money’s gone, that’s cut. It started making me not only become aware of what people were doing, but also aware of how underfunded it was. And then it made me ask the question, ‘Well, why is that?’”

He would like to be able to claim, he says with a smile, that the 1980s miners’ strike in Port Talbot when he was a teenager were his political awakening. But “I can barely remember it, because I was in my full obsession with acting and youth theatre. That’s all I thought about.” His mother was a secretary, and his father worked his way from the factory floor to middle management at the steelworks. “I always felt like we were doing all right, but in retrospect we were barely getting by.” Not that he gave it much thought, but he considered his family middle class – until he got to London, to study at Rada.

Sheen’s 20s and 30s were about building his career: huge acclaim in the theatre, then in films such as Frost/Nixon. He became known for inhabiting diverse real-life characters, from Tony Blair, twice (in The Deal, then in the 2006 film The Queen), to Brian Clough (in The Damned United in 2009). He was in a bit of a Hollywood bubble, living in Los Angeles where his daughter, from his former relationship with the actor Kate Beckinsale, was growing up. Then came The Passion, which brought him back in touch with his roots. Sheen was at a point where his career had brought him respect and a degree of wealth. “I wasn’t just desperately trying to get on and establish myself,” he says. “I was able to look out a bit more.”

There were other flashpoints. Visiting a refugee camp with Unicef, he watched a hungry child pick grains of rice out of caked mud; feeling wretched, Sheen asked how soon he could get money from his bank account to that specific child, and was told it didn’t really work like that. It had a profound effect. “I remember making a kind of a deal with myself and saying …” His voice breaks and his eyes well up. “I’m not going to get money to that kid, but I could only not do that if I’m then going to do something else. Going, ‘Right, I can see that there’s a way of walking away from here, going home, back to your life, and no one’s going to blame you. But you’re not going to do that.’”

Being wilfully blinkered wouldn’t necessarily have been the easy option. “I suppose that’s how you end up eating yourself from the inside. So no, I would say this is the easier thing.”

When he moved back to Port Talbot, one of his projects was the 2019 Homeless World Cup; Sheen led Cardiff’s bid to host the annual tournament, bringing together 500 players from 50 countries, all of whom had experienced homelessness. When the funding fell through, he ended up selling his houses in Los Angeles and Wales to pay for it. “At first, I thought it was the end of everything. I mean, I had nothing left. Not just that, I was in massive debt – I’m still paying it off.” It was frightening he says; his partner, the actor Anna Lundberg, was pregnant with the first of their two daughters. She was on board, he says. “Anyone would have been in their rights to go, ‘Sorry, I didn’t sign up for this.’ It could have gone either way, but I’m very glad that it went the way it did. I just couldn’t have got through that without her.”

He realised that, financially, everything he had built up had gone. “But there was something very liberating about that as well, but only because I realised that I had a support, a safety net.” He was in demand as an actor, with good earning power. And how much money did he really need anyway?

Still, he would look at other actors who had had similar careers to him, “and I look at what they’ve got, and I haven’t got that. But I made a choice, and I’m very happy with the choice I made.” He survived losing his money. “I learned a lot from it – about myself and about what matters to me – and I learned that that’s not the end of the story. For me, it was sort of the beginning of the story.”

There have been unexpected consequences. I wonder if living in Port Talbot rather than Hollywood, and not hoarding astronomical wealth, has helped Sheen’s work. Not to overstate his normality – he’s still feted, does glitzy events, and gets to work on big Amazon Prime shows such as the forthcoming final season of Good Omens – but surely hearing stories of people’s struggles, and seeing the very real effects of poverty in his community, must affect his work? It has, he says, “given me a different kind of emotional connection to what I do. I find myself more emotionally available in my work than I was maybe when I was younger. So, completely selfishly, it’s made me a better actor as well – but that wasn’t something that was conscious.”

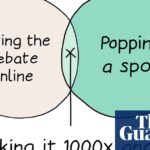

The other effect, he says, is feeling less powerless. “I think one of the most destructive things about the way we live now is that we’re constantly surrounded by injustice or a sense of things that are not right, and yet feeling like we can’t do anything about it. I’ve learned that by engaging in whatever way it is, it at least allows you to feel like you’re doing something.”

It highlighted to Sheen that because he had the potential to earn a lot, his debt came with manageable interest rates – something that wasn’t available to friends and family struggling with high-cost loans and credit. In the documentary, he meets a woman who runs a community gym and had used a credit card to cover basic needs, but the interest meant she could barely make a dent in the repayments. Sheen hopes the film will break down some of the myths, “that somehow, with people who get into trouble with debt, it’s because they’re making extravagant choices that they can’t afford. By talking to people who are working, maybe working two jobs – these are people who are incredibly resourceful, incredibly resilient. They’re not going on extravagant holidays or anything like that. It’s just basic.”

“The system doesn’t work any more,” he says. “But people find it easier to imagine the end of the world than something that’s a credible alternative to capitalism. I think people really feel there’s something intrinsically wrong and flawed with the system, and recognise that it needs radical change, but the only people who are offering radical change are people who are dangerous. And there’s no good end to that.”

He knows his “heist” is attention-grabbing, “and also hopefully helps the 900 or however many people that we’ve actually been able to get rid of some of the debt. But it’s also about: how do you create change and do something that can help thousands or millions of people?” The Fair Banking Act is one solution, which would essentially encourage banks to offer affordable credit to people previously excluded based on their income, background or where they live.

Putting up his own money, Sheen says, is important. “It shows that you’re serious about what you’re doing, but it also encourages other people to take that step.” It’s the same, he says, when it comes to being so public about it. “I’ve heard people say, ‘He can’t be that selfless, because he’s letting everyone know he’s doing it.’ That’s something I had to think about, and I made a conscious choice.” He knows he can offer his profile and cash, bringing attention to issues. “I never feel like it’s about me – mainly it’s about working with other people or highlighting what they do. I’m not doing it because I want people to think I’m great; I want us to be able to imagine an alternative to this, because this doesn’t work.

“And in my own little way, I’m trying to create my own alternative. It doesn’t have to be the way it is.”

Michael Sheen’s Secret Million Pound Giveaway is available to watch and stream on Channel 4 from 9pm on 10 March.