Though it’s now two decades since Andrea Dworkin died, her widower John Stoltenberg still finds it difficult to talk about her. “I sometimes break down,” he warns me, his mellow voice bumpy for just a moment. In a way, of course, she’s all around. He has stayed on in the Washington DC condominium where she died (he lives there with his husband of 15 years, Joe Hamilton); her books and music – she loved country – are a constant reminder of the life they shared. But her absence is deeply felt nonetheless. “It was a huge loss. Sometimes, I turn to her work just to hear her voice again. I connect to the way her mind was working, and I kind of invent a conversation with her.” In truth, it’s a blessing that she was a writer. In 2005, at the mortuary to discuss her cremation, he heard the horrible word “cremains” for the first time. “In that moment, I had the insight that Andrea’s remains would really be her words. They live on as she doesn’t.”

At first, admittedly, those words continued to be read only by a select few. At the best of times, Dworkin was a polarising figure, her uncompromising feminism despised by right and left alike (the right insisted she was a man-hater who believed all sex was rape; on the left, sex-positive feminists loathed her crusade against pornography). But slowly, this changed. “She joined several zones of conversation,” as Stoltenberg puts it. First, the scholars started working on her, devoting chapter after chapter to Dworkin in their academic books. Then, a new generation of feminists began rediscovering her. “I’ve subscribed to a service that tracks mention of Andrea, and I really shouldn’t spend so much time with it, because it giveth and it taketh away,” he says. “I mean, people still write the most vile stuff about her. But there’s also the most amazing engagement and rapture around her work, especially from younger women. Only yesterday, I came upon her entry in the Urban Dictionary…” With a smile, he reads it to me. It calls Dworkin “the most iconic radical feminist EVERERRR” and deploys several exclamation marks for emphasis.

Her time, it seems, may have come at last. Next month, three of her books will be published as Penguin Modern Classics, a literary imprimatur that puts her in the company of Simone de Beauvoir and Virginia Woolf – and Stoltenberg, the keeper of her flame, could not be more delighted (not even Zoom can dim his radiance). “She had such a struggle getting published in life,” he says. “There were brave editors along the way, but there were also campaigns to destroy her reputation, especially around her position on pornography. It made her a pariah in the publishing industry here: that’s why several of her books were published in the UK first. So to have these new editions come out at the same time, and for them to be so beautifully packaged [their covers feature work by the American feminist artist Judy Chicago, who’s also enjoying something of a renaissance]… It feels like a vindication. It’s thrilling and emotional, and though she always anticipated that if she was ever going to be acknowledged, it would only be after she was gone, I wish she could have seen it for herself.”

When Dworkin died of heart disease at the age of just 58, feminist Gloria Steinem likened her to an Old Testament prophet “raging in the hills”. Her friend, she said, often saw what was about to happen before others did – and it’s true that the titles Penguin has chosen to reissue do seem now to have been unnervingly prescient. If her first book, Woman Hating (1974), and the later Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1981), speak to a culture that has only grown the more violently misogynistic since they were published – their arguments have new urgency in a world of “incels” and 24/7 porn – then Right-Wing Women (1983) has plenty to say inadvertently about the devotion of Donald Trump’s female supporters, even after allegations of sexual misconduct were made against him. “Right-Wing Women is predictive of how women flocked to the patriarchy in the form of Trump, becoming his chief cheerleaders,” says Stoltenberg. “This a movement that’s devoted to defending the idea of real men – an idea which, as both Andrea and I have written, is a dangerous fiction.”

Does he think Dworkin’s jaw would be swinging in disbelief at the first flourishes of Trump’s second term, or would she have seen it all coming? “Oh, I think she would have believed it,” he says. “I often imagine what she might be saying or doing if she was here now, and I think she would have been very engaged; I don’t think she would have sat out his first term, and I don’t think she would be sitting out this one either.” The world looks very different to the way it did in 2005; George W Bush, abhorred by liberals at the time, has a whole new complexion thanks to Trump.

But some things never change. “I was glad when Andrea was done with her pornography project. She worked from VHS tapes, magazines and books, and a lot of material accumulated in the house, to my discomfort. But she found the DNA of pornography, and though that DNA has since been replicated with new technologies and vast circulation, on to handheld screens and so on, the central core of how it works is no different. Her insight was into the acculturated male brain and body, and that hasn’t moved much. The power relationship between men and women hasn’t really shifted at all.”

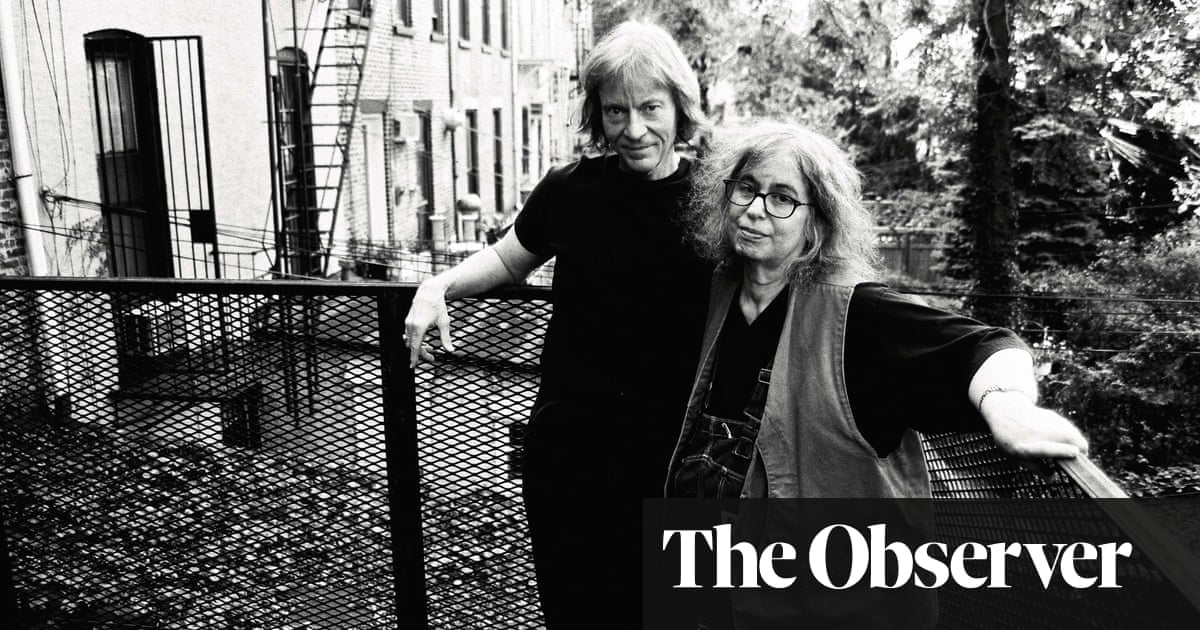

Stoltenberg, who is now 80, shared his life with Dworkin for 31 years. When they met, he was in his late 20s and a member of an experimental theatre company: they were introduced by its artistic director. (“Ha, there was a time when I thought I was in love with them both!” he says.) Things were certainly changing – it was 1974; hair was long and jeans flared – but he hadn’t yet come out, or not properly. “I’d told a few people I was homosexual – I think that was the word I used – but I hadn’t done a whole lot with it. I’d previously been married to a woman; I’d believed the relationship would straighten me out, and there was no one around to tell me that it wouldn’t.” With Dworkin, though, he could be “transparent”, in part because by this point she identified as a lesbian.

Their first encounter was at a meeting of the Gay Academic Union in New York, but it was only later that they talked. “We were at an anti [Vietnam] war poetry reading in Greenwich Village; our mutual friend the artistic director was up on stage reading from [Chilean poet] Pablo Neruda when suddenly the poetry turned hateful towards women. I was uncomfortable, so I walked out, at which point I discovered that she’d walked out for the same reason. That was our first connection.” Things moved fast. It was April. By June, they’d decided to live together, a momentous decision for them both. “I was in transit a lot, because I lived on the Upper West Side, and she lived on the Lower East Side. But one day there was a party at my place: I seem to recall it was to mark the birthday of Elizabeth Cady Stanton [a leader of the US women’s rights movement in the 19th century]. I drank way too much. I went into my bedroom, where I pretty much passed out. She came to check on me, and in that inebriated moment, I realised I couldn’t live without her.” He shakes his head, mournfully. “In a way, it’s a sad story.”

What was she like? In the media, Dworkin’s mushroomy tabards and denim dungarees combined with the reporting of her more extreme utterances to fix her in the public imagination as a half-crazed Valkyrie. But Stoltenberg insists the reality was very different: “She was nothing like that caricature, and she wasn’t like her podium personality either [at marches, she was known for her oratory]. In her private life, she was gentle and sweet and funny.”

Was he a feminist when they met? He thinks about this. “I’m racking my brain… But, no, I believe it was Andrea who introduced me to it. In particular, it was hearing her tell me of the abuse she’d received that was mind-blowing because it was completely outside my frame of reference [Dworkin had been molested by a stranger as a child; her first husband, a Dutchman whom she married while living in Amsterdam in the early 70s, was so violent, he would knock her unconscious]. I didn’t know anything about wife battery, and I didn’t know anything about rape, and when she told me, I realised I didn’t want to be any of those men.”

What was their relationship like? “Well, we knew from the beginning we weren’t going to be monogamous,” he says. “But we did have a life together that was deeply sensual: it was physically affectionate, as well as intellectual. I mean, she died in my arms…” It all sounds terribly modern. Did they feel they were pioneers? “No, not really. We weren’t public about it. There was nothing about us that was trying to be instructive, and I also don’t want to leave out the fact that there was a lot of animosity towards us. When we lived in Northampton, Massachusetts, a city some people call the lesbian capital of the world, we would walk along the street holding hands, and women would hiss at us, and gay men would pass us and just… settle their scorn on us.” Why? Were he and Dworkin supposed to have betrayed some kind of gay ideal? “I guess I don’t know. But there was a lot of imputation about it.”

Living together worked well. They shared household tasks – he cleaned the fridge, she dealt with the cat litter – and their working hours were highly compatible (Stoltenberg began writing, too, and has since published several books about the politics of masculinity). “I wrote in the morning on several cups of coffee; she would start at midnight, working on till dawn.” His apartment – she moved in – was Dworkin’s first safe home, and she cherished it. “That with-floor walk-up [apartment] on the Lower East Side was pretty vulnerable, and in Europe she’d effectively been homeless.”

Did he worry about her safety? “Yes, especially when she travelled for speaking engagements. The world was hostile to her in a way that it wasn’t to me.” Did her activism take a toll on her health? The second-wavers who first inspired her – Shulamith Firestone, Kate Millett – seemed in the end to suffer for their feminism. “She didn’t experience problems with her mental health, but her work was hard on her. Most people shy away from looking at certain things, myself included. But she went in there.” When she finished Scapegoat: The Jews, Israel and Women’s Liberation (2000), a book that dealt with the Holocaust – Dworkin was Jewish, and once said she would have been a rabbi had she been allowed – friends urged her for her own sake to stay away from atrocity in the future.

He and Dworkin always said they would not marry unless one of them was terminally ill, or imprisoned for political activity. But in 1998, they did: as his wife, she would be covered by the health insurance that came with his then job. “We were on vacation in Florida; some friends had let us use their home. I was reading some tour literature, and I said: ‘Hey, look at this. The state of Florida has no waiting period on marriages. You can just walk into a justice of the peace and get married.’ We thought: why not? We didn’t tell anybody except immediate family. It was as unceremonial as it could be. The justice of the peace said: did you pick her up out in the parking lot?”

By now, however, Dworkin’s health was beginning to fail. “She’d had several major surgeries, including bariatric and knee replacement. I was at the point where I was terrified that I couldn’t take care of her any longer. I think she had that fear, too. We didn’t discuss it, but I was her carer…” His voice tails off. Her death was both sudden, and expected. How did he feel about the public response to it? “I guess I was pleased. There was an outpouring, some very deep expressions of connection and gratitude for what her work had meant to women.”

After so long, he was inured to any commentary that was less kind. “Somewhere along the line, I developed a kind of muscle for sorting out what crap people said about her. I learned to notice the way in which whatever they were saying revealed more about them than about Andrea. Anyone who engages with her work always reveals something of themselves.”

For some, Stoltenberg is a controversial figure. He has said that Dworkin would have been a trans ally had she lived, while others – the feminist activist, Julie Bindel, who was a friend, is one – have accused him of misreading her work for his own ends in this regard. But we don’t discuss this today. How can anyone really know? As Steinem said after her death, even in life, she was “frequently misunderstood”; better to talk about the latest editions of her work, and whether they’ll bring her new readers. Will they? This is his hope. “Her history, her experiences, weren’t uncommon; they were, and are, more common than people will admit. But the way she universalised them was uncommon. She looked at the world through the lens of her life without fear.”

-

Woman Hating, Pornography and Right-Wing Women are published by Penguin (£10.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copies at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply