Lukhanyo Calata’s first memory of his father was the funeral. His mother sobbing, the earth beneath his feet shaking from the number of people gathered at the graveside, and the fear he felt aged three as the red box holding his father, Fort, was lowered into the ground.

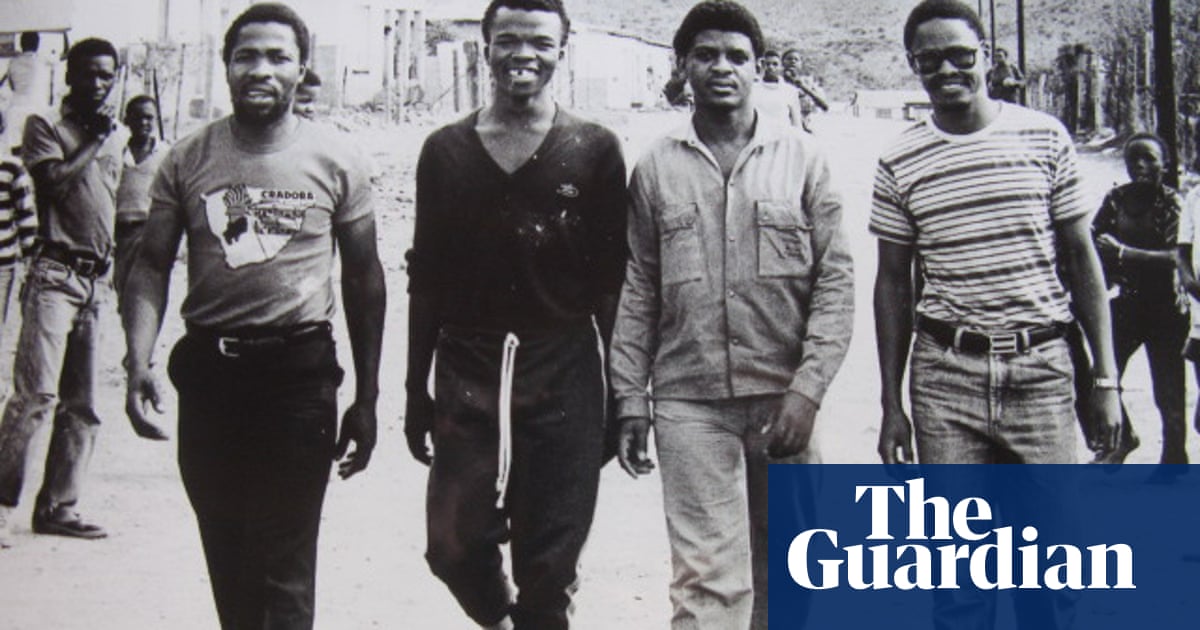

Fort Calata was one of four men stopped at a roadblock in June 1985 by security officers. The Cradock Four were beaten, strangled with telephone wire, stabbed and shot to death in one of the most notorious killings of South Africa’s apartheid era.

In 1999, the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) denied six security officers amnesty for their role in the killings. They were never prosecuted and have all since died.

Now, as part of a group of 25 families and survivors of apartheid-era deaths and violence, Lukhanyo Calata is suing South Africa’s government for failing to bring his father’s alleged killers to court.

“Losing my father has impacted every fibre of my being,” Calata said. “We were ultimately betrayed by the people that we trusted to lead us into a new society.”

Calata’s case, filed at the high court in Pretoria this week, demands an inquiry to establish why there were no prosecutions. It also asks for “constitutional damages” of 167m rand (£7.3m) to fund further investigations, litigation, memorials and public education.

A spokesperson for South Africa’s justice minister, who was named as a respondent in the case, said: “Our legal section is reviewing the documents and will respond accordingly, adhering to due process. We will collaborate closely with the National Prosecuting Authority and the presidency on this matter.”

The justice ministry reopened an inquest into the Cradock Four killings last year, but proceedings were delayed until June.

“The TRC cases were deliberately suppressed following a plan or arrangement hatched at the highest levels of government,” Calata alleged in court papers.

In 2021 a supreme court of appeal judgment found that “from 2003 to 2017, investigations into the TRC cases were stopped as a result of an executive decision” and that “this was indeed interference with the NPA”. The court added that there was an “absence of detail as to why it occurred”.

Thabo Mbeki, who was South Africa’s president from 1999 to 2008, said in a statement in March 2024: “During the years I was in government, we never interfered in the work of the NPA. Instead of propagating falsehoods, the NPA must investigate and prosecute the cases referred to it by the TRC.”

Nombuyiselo Mhlauli was reluctant to speak about the new legal case. She preferred to talk about her husband, Sicelo Mhlauli, who was killed alongside Fort Calata, Matthew Goniwe and Sparrow Mkonto, and the impact his loss had had on her and their two children.

“We were so close to each other,” she said. “I depended on him so much.”

“He was such a friendly person, who liked to joke a lot, full of laughter all the time,” said Mhlauli, who like her husband was a teacher. “Wherever you find him he is laughing and the other people around him are laughing a lot.”

After her husband’s killing, Mhlauli was harassed by security forces, who would regularly kick down her door at night, until she fled in 1989 to Cape Town, where she still lives.

So, when Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990, before going on to be South Africa’s first black president, Mhlauli was excited.

But the fact that the Cradock Four case has not been prosecuted while Mandela’s African National Congress party has been in government “left us so hurt and bitter”, she said. “I wish the government would come forward and tell us: why did they delay the process?”