Years ago, a pediatrician told me a story about vaccinating one of his patients. He had carefully drawn up the dose, flicked away the bubbles, and was about to administer the needle when the child suddenly started seizing. Everything ended up fine, but had the seizure started seconds later, could anything have convinced the mother it wasn’t because of the vaccine?

Vaccination is a miracle of modern medicine, but there’s still something bizarre about being jabbed with a weakened pathogen – or some other mysterious substance. To get vaccinated, then, is an act of trust.

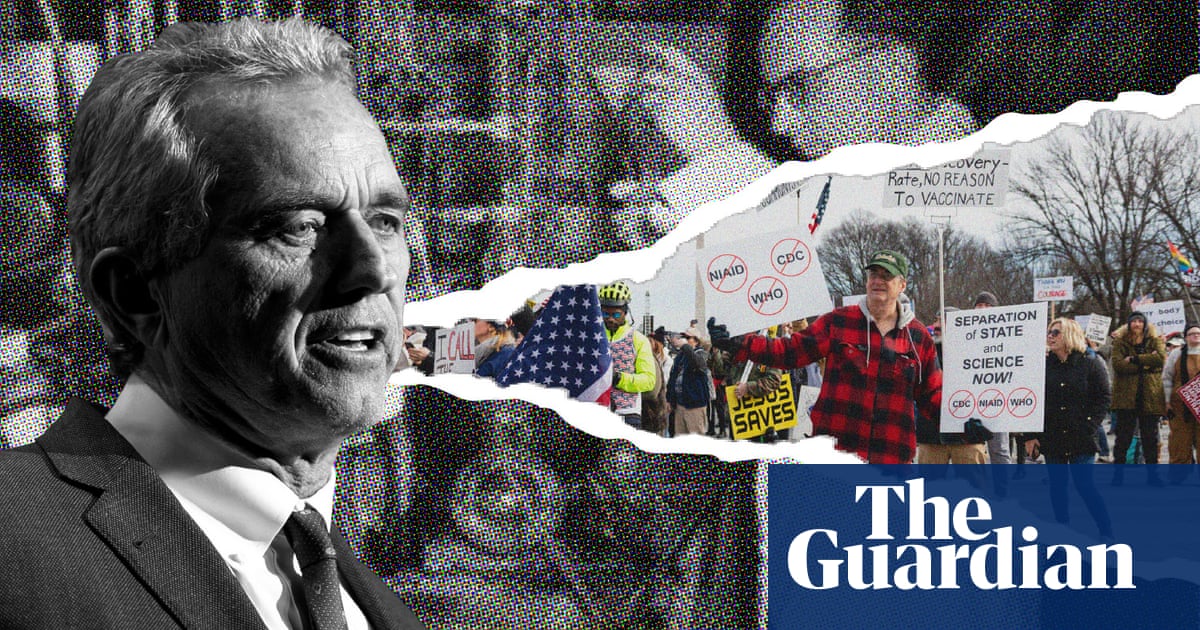

It’s bewildering that America’s most influential vaccine skeptic, Robert F Kennedy Jr, has been nominated for our nation’s top health post. He is on the record as having previously said: “There’s no vaccine that is safe and effective,” and intends to investigate a supposed link between vaccines and autism.

While there are various ways RFK Jr could weaken vaccination programs, Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist at Yale School of Public Health, is especially worried about the growing storm of fear. “What’s detrimental much more quickly is individual-level decisions not to get kids vaccinated based on rumors, falsehoods, or confusion,” she said.

As misinformation gains ground in the White House, physicians and science communicators are scrambling to set the record straight. Figuring out the best way to do this might be key to preserving decades of public health progress – and preventing the next pandemic.

Reconnecting with the public

“There’s always been people pushing back against science information,” Deborah Blum said – from evolution to cigarettes to the climate crisis. “Today it’s reached a new intensity, and a lot of that is driven by the politics of the moment.”

Blum, a Pulitzer prize winner and the director of the Knight Science Journalism program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said: “People feel that science is this powerful source that is jerking them around and telling them what to do and making them feel stupid.” As a result, many Americans walk away from the proverbial science campfire, asserting some agency in their disbelief.

This disconnect was on full display last month, when 77 Nobel laureates signed a letter urging the Senate to reject RFK Jr’s nomination. They argued that placing him in charge of the Department of Health and Human Services would “put the public’s health in jeopardy and undermine America’s global leadership in the health sciences”.

Their indignation had little to no effect. “That was a very illustrative example of science people being unable to reach the non-science people,” said Dr William Flanary, an ophthalmologist who makes short-form healthcare videos. “It’s just talking to each other, not being relatable at all.”

Under the alter ego “Dr Glaucomflecken”, Flanary uses comedy to trick people into learning about the healthcare system, and has more than 4.5 million followers across TikTok, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook. (More than half of Americans get their health information from social media, with Facebook especially popular in rural communities.) It’s a one-man show, with Flanary donning his grandfather’s tweed blazer to play a psychiatrist, a unicorn headband for a pediatrician, or a pair of headphones with a Sharpie “mic” for an insurance representative.

“If you take those same topics and you try to be straight about it, you’re going to immediately turn off a lot of people,” Flanary said. Truth is often more boring than misinformation, but by keeping his videos funny and short – “no one has an attention span anymore” – he can hold people’s attention and begin to change their minds.

Blum agreed with Flanary that echo chambers are an issue. “When we’re looking at the media landscape at the moment, it’s a thousand shards of glass, and everyone, for the most part, exists in a different shard,” she said, referring to an Axios piece about the decline of traditional media.

One approach to win back trust is thus to traverse this mosaic and meet people where they are. Richard Tofel, the former president of the investigative publisher ProPublica, said: “Scientists don’t need to confine themselves to traditional channels: they should be talking about science on TikTok, through ethnic press, through Sunday morning television shows.”

Jetelina, for example, has her own newsletter, Your Local Epidemiologist, with more than a quarter of a million subscribers. “They’re not the Joe on the corner,” she said (about 70% of them have an MD or PhD), “but they are trusted messengers, who take my information and curate it for their patients, for their congregations, for their businesses.” And readers trust Jetelina because she humanizes science in a way that feels impossible with legacy media.

“They see my vulnerabilities, making mistakes and owning up to them,” Jetelina said. “People don’t trust brick walls; they trust other humans.”

Fostering dialogue

Indeed, it’s not enough to simply diversify the medium without also fostering meaningful dialogue. “Living in 2025, we’re abundantly saturated in media,” said Elijah Yetter-Bowman, a science documentary-maker and founder of Ethereal Films. “The only way to separate the piles of videos is through the additional element of personal human interaction.”

In 2023, Yetter-Bowman released Burned: Protecting the Protectors, a documentary about cancer-causing forever chemicals inside firefighter’s protective gear, and screened it at a summit of the International Association of Fire Fighters. “The circumstances where we were coming in was either full distrust or complete uncertainty,” Yetter-Bowman said, given “corporate sham science” about forever chemicals’ risk, and the union previously denying there was an issue.

But with the support of the union’s new president, Yetter-Bowman showcased his work to 2,200 fire chiefs and hosted a Q&A to help digest the film. “This sharing of space with that community was an essential component of the massive mind shift, not something that simply uploading a video online could ever achieve,” Yetter-Bowman said.

The union ultimately announced that removing forever chemicals from firefighter gear was their number one priority – and took Yetter-Bowman’s team on tour across hundreds of fire stations nationwide to screen the documentary.

Beyond direct engagement, another way to create human connection is by keeping science communication hyperlocal. After all, local newspapers, television and radio stations are the most trusted media in the county, with 85% of Americans saying the local press is essential for democracy.

It’s because these reporters are from the same communities they’re writing about, said Erika Hayden, director of the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz, enabling greater transparency and authenticity. She gives the example of Lookout Santa Cruz, which won a Pulitzer prize last year for its coverage of catastrophic flooding and mudslides in the area. “They know what people are concerned about, and they were really able to dig in and dedicate resources,” Hayden said.

Too much of science communication is focused on the rich and powerful, echoed Blum, but local journalists flip that model. She gives the example of Mike Tony, a science reporter for the Charleston Gazette-Mail in West Virginia who said: “I’m writing for my neighbors, and I care about them. And we have to help each other.”

Tony knows what resonates with the community – how climate crisis stories need to be focused on his neighbors but also how he should never use the words “climate change” since that will immediately turn them away. “When you’re parachuting in from New York or San Francisco, you don’t necessarily do or know that,” Blum said.

Investing in local science journalism is therefore key to rebuilding trust and bringing people back to the science campfire. Blum and Hayden are hopeful the landscape will get better, given the rise of successful digital startups like the Maine Monitor and VTDigger, as well as a half a billion-dollar infusion into local news from the MacArthur Foundation and other partners.

Not being condescending

Building trust also requires humility. “When we feel under attack – people who in believe in vaccines, people who believe in fluoridation – you get a circle-the-wagons response: ‘Don’t worry your pretty little head about it; there’s no risk at all,’” Blum said.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, public health agencies tried to project such confidence, playing down the risk of everything from breakthrough infections to myocarditis, despite the truth being more complicated. For example, it was relatively common to get Covid-19 after being vaccinated, even if such cases were less likely to lead to hospitalization and death. Similarly, the second dose was indeed associated with myocarditis in teenage boys and young men, even if the risk of getting this heart condition was higher if they got Covid-19.

Blum emphasized the importance of honesty and taking people’s concerns seriously. “If we dismiss reality, which is that everything bears risk, we do ourselves no favors,” she said. “How do you trust these mysterious people that you’ve always been told are smarter than you? And when do you start mistrusting them?”

Part of this requires science communicators to listen to the questions of people on the ground and respond with empathy, Jetelina said. The evidence shows that vaccines do not cause autism, but what’s really behind the rise in cases (from one in 150 in 2000 to one in 36 in 2020)? And that answer should ideally go beyond a hand-waving dismissal that it’s all just greater awareness and diagnosis.

“We don’t know why autism rates have been increasing, although we have a lot of hypotheses,” Jetelina said, such as air pollution, vitamin D deficiency, gut inflammation, toxic chemicals and childhood infections. Acknowledging what we don’t know – and how scientists are working to find out – is key to rebuilding trust.

“In my experience with Burned and how this can be carried forward to vaccines, it is personal experience, vulnerability and human connection” that make the difference, Yetter-Bowman said. For example, a documentary trying to reach vaccine skeptics might focus on cases of parents whose kids became quite ill after not being vaccinated, while also exploring concerns about pharmaceutical companies and regulatory bodies.

“To paint a single-sided story is more likely to create bias and distance audiences,” Yetter-Bowman said. It isn’t about false equivalency but being empathetic – and strategic.

This has been an important shift in Flanery’s own content creation, “not directing ridicule or satire on people who ultimately are powerless” – like the healthcare workers he gently mocked for refusing to get vaccinated – but focusing on the institutions and corporations in control. “Most of us are powerless in the face of the pressures we have in the healthcare system,” Flanery said.

Reason for hope

While all these overtures are important, Jetelina and Tofel both emphasized that it was important to remember that the vast majority of people still trust and support vaccines.

For example, 93% of kindergarteners were up-to-date on their childhood vaccines during the 2023-2024 school year. (For highly contagious diseases, herd immunity thresholds range from 80% for polio to 95% for measles.) While the country may be entirely polarized on politics, “it would be a very big mistake to characterize 90-10 as another manifestation of 50-50,” Tofel said. Vaccine hesitancy may grab headlines, but it’s not the prevailing sentiment.

Still, in a world where misinformation spreads faster than truth, what Jetelina and Tofel want to see is more scientists entering the fray with curiosity and care. “The people who are not at my campfire, who don’t have all the resources and money and feel disenfranchised,” Blum says, “you’re the audience I want to reach.”